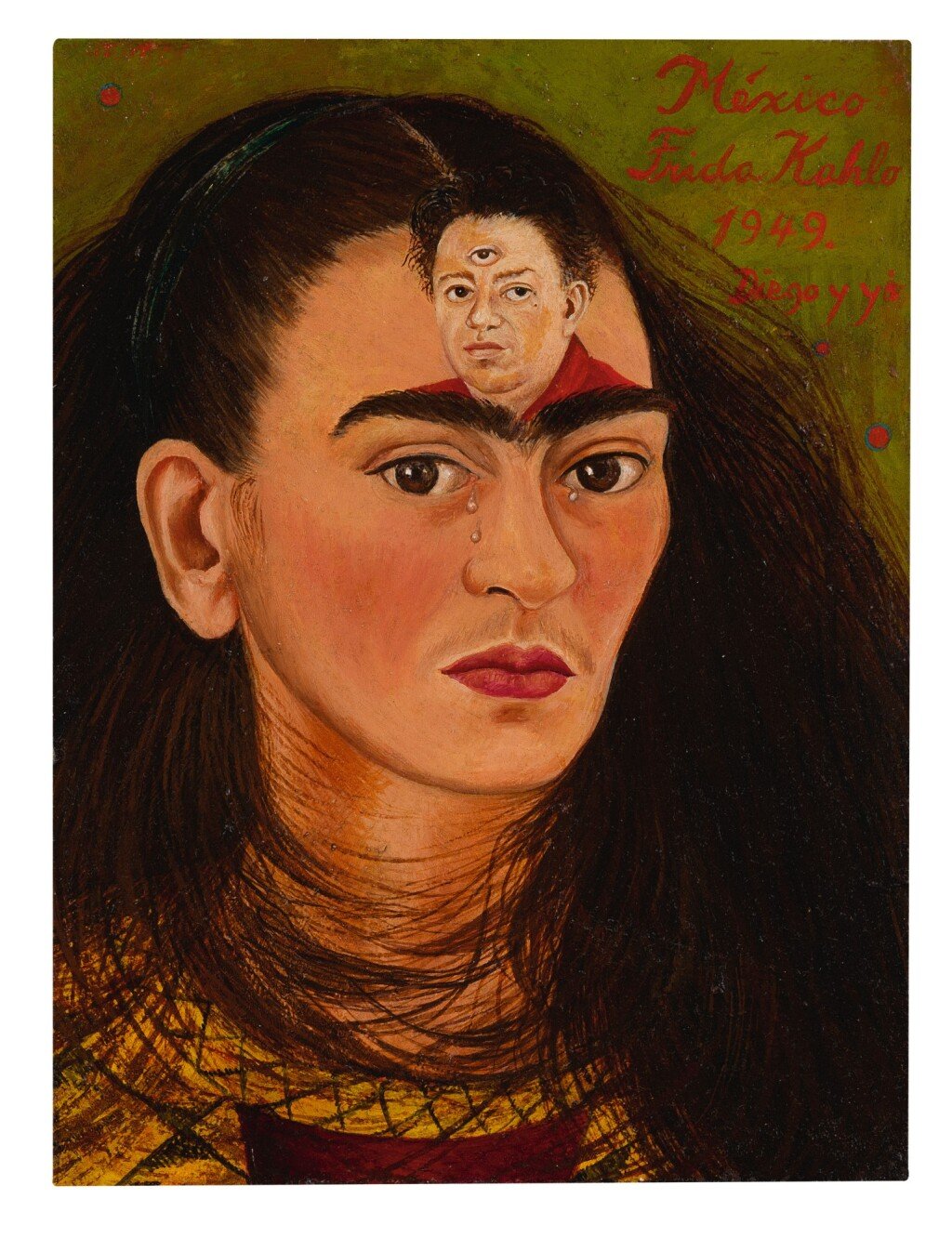

History was made on Tuesday, November 16th, when the self-portrait of Frida Kahlo, “Diego and I,” painted in 1949 broke records as the most expensive Latin American artwork ever sold. Sotheby's estimated the price of the painting between 30 and 50 million. In the end, it was sold to Eduardo F. Costantini, founder of the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA), for $34.9 million dollars.

In 1990 Kahlo became the first Latina woman to sell this same painting for more than $1 million. Then, in 2006, Kahlo made history again when Sotheby's sold another of her self-portraits, “Roots” painted in 1943 for $5.6 million. There is an average of 200 works that Kahlo completed during her lifetime. Although 200 seems to be a high number, in reality, it is a limited number of artworks. It’s speculated that during the next few years, these works of art will continue to increase in value.

Despite all the success that her artwork now has, Kahlo remained unknown to the art world until shortly before her death in 1954. In contrast, her husband Diego Rivera was a famous artist and received commissions for murals around the world. In 1933, during a commission in Detroit, Michigan, Kahlo met Florence Davies, a reporter for the Detroit News. In recent years, the article written by Davies has resurfaced despite being published 88 years ago. At that time, no one could have predicted the immense success that the 25-year-old girl would have.

The article has been circulating on social networks, specifically for its sexist title. Some people think it wasn’t Davies who chose the title, "Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art," as it seems to belittle the talent of Kahlo. Although the title underscores Rivera's success and emphasizes their marriage, the article contains quotes from Kahlo with her unmatched sense of humor saying, “Of course, he does pretty well for a little boy [Rivera], but it is I who am the big artist,” referring to her husband as she laughed out loud.

Kahlo's confidence in that interview seems to foreshadow her career. They were both artists in their own right, yet Kahlo has eclipsed Rivera in the art world and proved that she was much more than just Mrs. Rivera. Kahlo has established her name as one of the great artists of the 20th century. In Davies's article, she makes it clear that Rivera was never her teacher, she never even studied, she just started painting.

In 1925, after a tragic accident where Kahlo nearly lost her life, she took up art again during the time she was bedridden during her recovery. As a child, Kahlo retouched the photographs that her father, Don Guillermo Kahlo, took. That's where Kahlo developed her artistic technique and attention to detail.

“Diego and I”, like most of her works, is an account of her personal afflictions. In it, we can see Frida with a penetrating gaze as three tears fall from her eyes. Her hair is loose and tousled, a contrast to the typical flowery-ribbon-braid hairstyle she used to wear. She gives the impression of a defeated woman with palpable vulnerability. Her hair is tangled around her neck creating a feeling of suffocation. On her forehead, perched above her iconic eyebrows, is the image of Diego as the third eye. Literally in her mind or infiltrating a higher wisdom beyond what her eyes can see. Diego also has a third eye on his forehead which seems to belong to him. It could be interpreted as if he is following his own intuition without being influenced by anyone else.

During this time it’s known of Rivera's infidelity with the Mexican actress, Maria Felix, who was also friends with Kahlo. Rivera's betrayal was a severe blow to Kahlo whose health continued to deteriorate. Kahlo's turbulent life ended at the young age of 47 when she suffered a pulmonary embolism. A year earlier, she attended her first solo exhibition in an ambulance. It’s considered that “Diego and I,” is one of the few works of art produced at the height of her artistic maturity.